“In tennis you’re on an island,” he writes. It’s telling that, for years, no one believed him - after all, slamming a fuzzy ball was making him millions - but the solitary existence on the circuit haunted him.

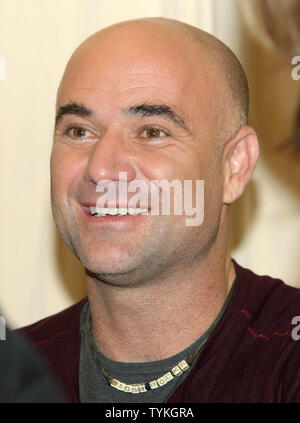

He confesses that he tanked certain matches.Īfter taking the court and winning without any underwear, he goes commando for the remainder of his career.Īgassi repeatedly notes that he “hates” tennis. Agassi acknowledges using crystal meth throughout 1997 and then lying about a positive drug test to avoid punishment by tennis authorities. “Open” is rife with self-damning revelations. Concerned that the wig would fly off, he played tentatively and lost to an inferior opponent. Worse, he offered excuses for every defeat.Īt the 1990 French Open, site of his first Grand Slam final, he wore a hairpiece to conceal his thinning hair.

One of his endorsements, which carried the unfortunate tag line “Image Is Everything,” came to represent what many believed was his essential flaw.īy turns angry, fragile and apathetic, Agassi routinely lost important matches and seemed unable to handle pressure.

(It was the 1980s.) The media interpreted this as the “real” Andre, the rebel without much cause. He donned denim shorts, wore an earring, and added frosted highlights to his mullet.

When Agassi turned pro, he had plenty of game and a teenager’s inarticulate bravado. The absurd scenes here describing Bollettieri’s academy, which Agassi calls a “glorified prison camp,” read like something from David Foster Wallace’s novel “Infinite Jest.” He’d dropped out of high school by age 14. In seventh grade, Agassi was shunted off to Florida to be tutored by controversial coach Nick Bollettieri. “No one ever asked me if I wanted to play tennis,” Andre Agassi writes, because “what I want isn’t relevant.” A prodigy who traded volleys with Björn Borg at age 8, he came to dread the ball machine, nicknamed “the dragon,” that his father concocted for endless hitting sessions.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)